The Fourth of July marks 10 years since scientists at CERN, the world’s largest research center based near Geneva, announced the existence of the Higgs Boson. A team of 6000 researchers working with the world’s first atomic splitter, the Large Hadron Collider.

The discovery of the long-awaited particle behind the origin of mass awarded François Englert and Peter Higgs the Nobel Prize for Physics. After 45 years after they proposed the theory, they dismantled the practical side as well.

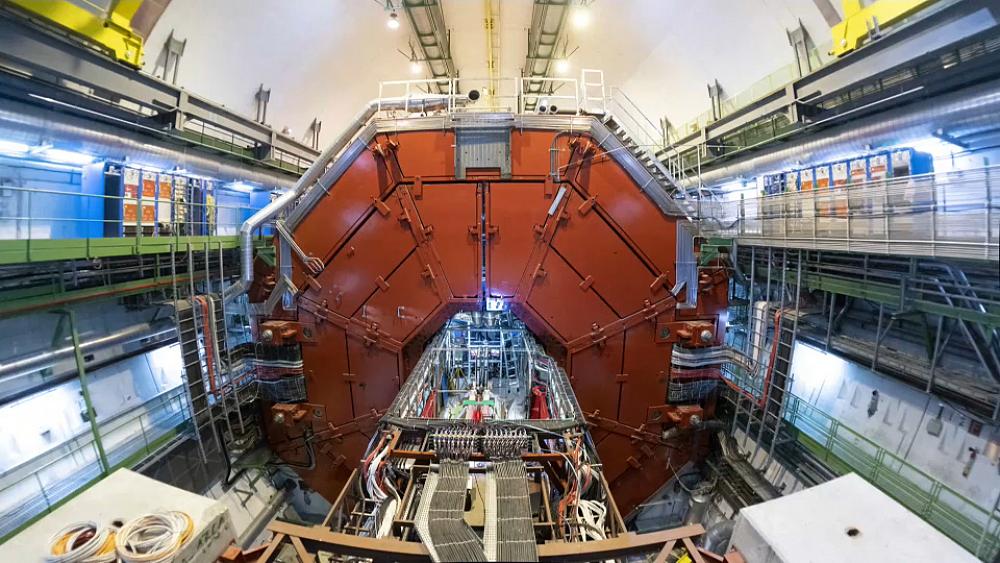

On this famous anniversary, CERN announced that it will restart the Large Hadron Collider, the machine that studies the origins of matter and the universe.

After a three-year hiatus from its research, CERN took time to update itself. On July 5, for the third time in its history, the Large Hadron Collider will restart to an unprecedented level of collision energy (13.6 trillion electron volts).

Delphine Jacquet, the engineer in charge of the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), explains the technical aspects that the team will make to continue the studies.

“We are going to put in a collision, for the first time, in the LHC, protons with an energy record of 6.8 tev per beam. At that energy, the collision would be at 13.6 tera-electronvolts (tev), and that would be a very nice record for the experiment.”

Jacquet continues: “From now on, the data from the experiment will be, for 3 long years, with the hope that we will have new discoveries and interesting things coming out of these collisions.”

Smashing the particles at near-light speed in an absolute vacuum and at the lowest temperature in the universe (a minimum of 271.3 degrees Celsius) enables scientists to gather data on how particles break apart and how they bounce off one another.

By restarting the Large Hadron Collider and studying the very small parts, physicists want to further push the boundaries of our knowledge in topics such as dark matter or antimatter.

As part of its promotion, CERN is charging itself for three of the five planned rides. They hope that collisions of particles together will produce billions of proton-proton collisions — potentially opening a new chapter in our understanding of the world.

“Wannabe internet buff. Future teen idol. Hardcore zombie guru. Gamer. Avid creator. Entrepreneur. Bacon ninja.”