How did hip-hop, a movement that was born in New York’s black neighborhoods, take root in France in the 1980s? How was it so well embraced here that it is now so dominant among millennials?

Through this terrifying and well-documented exhibition, curator François Gautret particularly wanted to show the abundance and great diversity of this multidisciplinary culture, as well as the media through which it maintains a fruitful dialogue, whether it be cinema, radio, fashion or photograph.

What is your personal relationship with hip hop?

Francois Gautret : I grew up in the 19th arrondissement of Paris, near the Pioneers, in Stalingrad. My neighbor next door was called DJ Abdul, and De Nastye lived in the tower next door. I didn’t discover hip-hop at some point, I was born into this culture. My brother, who is nine years older than me, listened to music, and the BBC graffiti buddies (the Bad Boy pioneers) came home, so I was immersed in this universe the whole time. Etant plutôt réservé de nature, je n’étais pas le maître du micro mais j’avais besoin de m’exprimer et j’ai trouvé ma voie très jeune : je suis entré dans la danse, dans le break, de à l’âge 9 years. In parallel with my studies, I joined the Quintessence dance company in 1996 and a little later accompanied DJ Double H – every time Cut Killer, DJ Abdel or Pone gave a concert, they invited us to dance. I created my own company in 1999, RStyle, with which I have been organizing all kinds of events around hip-hop in the broad sense for 22 years, such as the Urban Film Festival. By virtue of circumstances, I became an archiver of illustrated content and RStyle became a resource center, as people asked me to watch this or that movie that we could not find on the Internet. One of the difficulties I had in making the gallery was finding archives of rap clips in high definition. It’s very complicated, even music channels like MTV have thrown a lot of video masters. Archives are gradually disappearing and with it the hip-hop legacy.

Specifically, what’s the hardest thing to find that you’re particularly happy to offer?

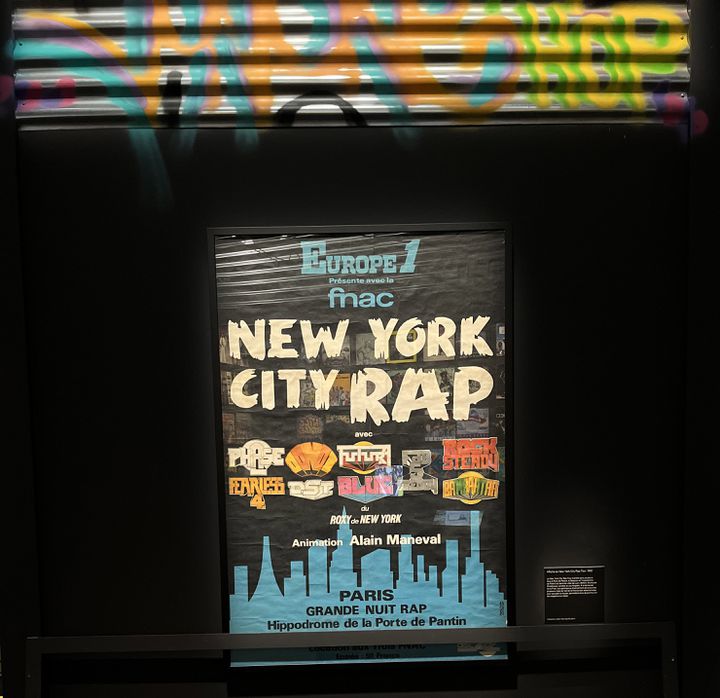

I’m especially proud to have found the NYC Rap Tour poster. This concert is the arrival of hip-hop in France with the Americans who landed 40 years ago at the Hippodrome des Pantins, almost at the venue of the Philharmonic! This poster was difficult to find because even Bernard Zechry, who organized the tour at the time, did not have it and did not know where to find it. We finally got the original in New York, at the World Hip Hop Museum in the Bronx. They loaned it to us and we brought it in specially for the occasion. To accompany him to the show, we’re showing an extremely rare video from his New York City rap tour. There is an excerpt from Megahertz where we see them express themselves in Bataclan with DST, Fab 5 Freddy, Rammellzee, Rock Steady, and another small movie, Rap, by Pascal Venturini. We’ve done a real groundwork to find content about this groundbreaking event that many have heard about without really knowing the details.

What is the most difficult to achieve this course?

I think the most difficult was to present the archival content in an original and interactive way. The scenography produced by Clemence Farel is wonderful, with corrugated iron, a reference to iron curtains, to the street, but in a rather quiet way. The idea was really to give a powerful dimension to things like the famous wasteland of the church where it all began. The audiovisual teams have also done a great job with the idea of 360: so we will be surrounded by archival images but enhanced by spatial sounds. When we’re at La Chapelle Waves Square we see the aerial metro going by on the right in the video but we also hear it on the right, then we have the graffiti artists painting on the left and we hear them on the left, so it’s really an experience for the visitor. I wanted to get away from the somewhat dusty museum and bring in a fun, action-driven, lively, and fun part, with ongoing programming into the exhibition spaces, performances, and fights. Seeing my little drawings come true today is the icing on the cake. The 360-degree audiovisual space was a dream, so it’s a pleasure to try it out.

Does hip-hop still need to be explained and legalized in 2022?

I think it is still misunderstood even though it is ubiquitous today. Hip hop is still frowned upon. The movement has always had to fight for everything. As a dancer, I’ve often had to say I’ve been doing contemporary dance, even if it’s just to make it to the ballroom. With the exhibition, I particularly wanted to show the diversity of the movement. Because we still tend to confuse hip-hop with rap, or with dance, they are only part of the whole. I also wanted to interest all generations. This culture persists because each generation reappropriates it, injecting it with its music, influences, and the origin and experiences of its representatives. But when everyone gets hold of it, we find everything and its opposite in this culture, and it’s just paradoxes: we can have the Zulu nation movement that advocates peace and unity, but we can also have the gangstarap movement. We can get mainstream and underground. You can have graffiti vandals and artists in galleries. We can get hardcore rap and poetic rap. From breaks to the Olympics and from breaks to fights or to Chaillot. We can be into the art of elegant clothing, but we can collaborate with luxury homes. Opposites do not cancel each other out, they respond to each other.

Other than the advisors you surrounded (author Vincent Piollet, journalist Yerim Sarr, director Frank Haderer), did you feel supported by the French hip-hop community?

If I were to be really honest, not everyone would really believe it. It was not always easy to mobilize the actors of the movement. Some had reservations such as: “The Philharmonic is the state, they never supported us, so why give them strength now? Etc.” Yeah, well, I get that, but at the same time it’s also an opportunity to put your foot in the door and why not improve things. I think everyone has their own hip-hop, their interpretation, everyone has their own experience and it was really important for me to put it all together. I feel like a little middleman. People who haven’t seen each other for a long time will meet at the show, it’s an opportunity to transcend disciplines too, breakers, rappers, graffiti artists, because in the end they rarely get the chance to meet. They all find together. The idea of 360 was to revolve around these major disciplines of hip-hop but also to show everything that exists: radio, cinema, photography, graphics and fashion. Hip-hop feeds on a lot of things and I definitely don’t want to split it up again. It was important to convey this and make it visible to an audience that might be tempted to lock it in clichés. Hip-hop is not one-dimensional, there is something for everyone. This is what we should be aware of.

“Hip-Hop 360” Exhibition

To watch at the Philharmonie de Paris from December 17, 2021 to July 24, 2022

Daily except Monday from 11 am to 8 pm and Friday until 10 pm.

(Exhibition closes on December 25 and January 1)

the prices : Free for children under 16, from €7 to €12 for others

Concerts, choreography, conferences and breakdancing are planned along with the exhibition from January 2022, consult the program

“Web specialist. Freelance coffee advocate. Reader. Subtly charming pop culture expert.”