On Tuesday, NASA engineers announced that the much-anticipated launch of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) was delayed “to no later than December 24.” (The mission was previously scheduled to take off on December 22 this year.)

This isn’t the first time in 2021 that the launch of the staggeringly complex telescope has been delayed – it’s actually the fourth time. The delay came this time due to “a communication problem between the observatory and the launch vehicle system,” according to A . Brief statement from the space agency.

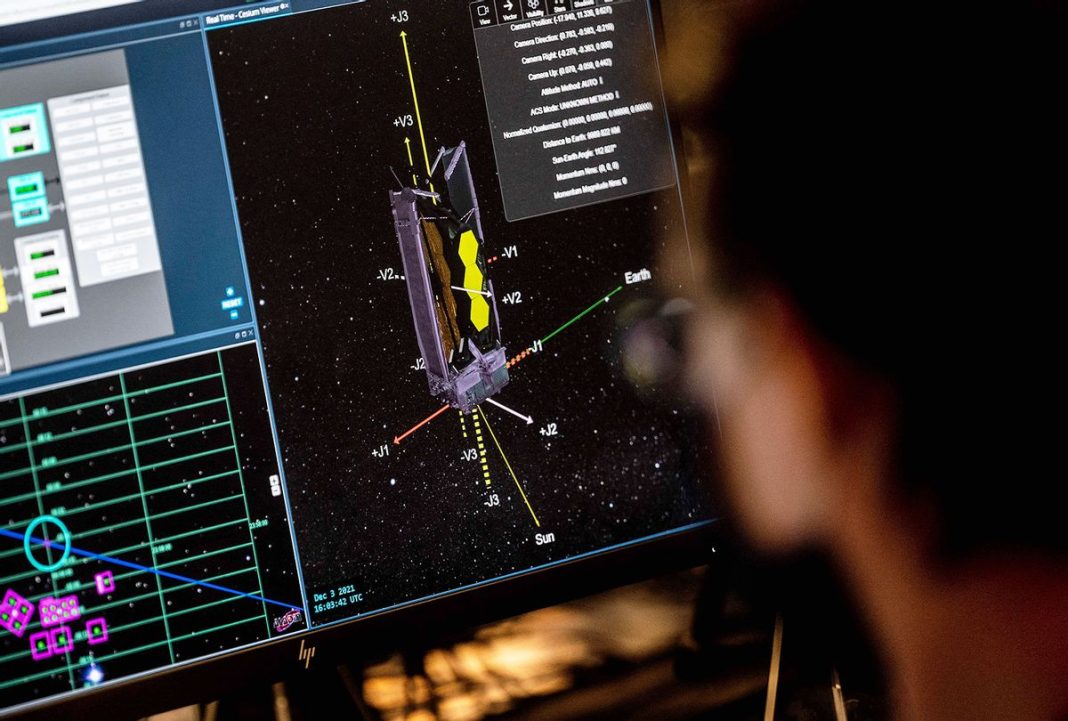

For those who don’t follow space news, JWST is a once-in-a-generation space observatory, preparing to start a new chapter in astronomy. It is also one of the most expensive space missions (about $9.7 billion) in history. As the successor to the Hubble Space Telescope, JWST will be launched on the front of an Ariane 5 rocket and will be flown to a location approximately 1 million miles above Earth’s surface. Once it reaches its final destination, in about six months, JWST will be looking into the far corners of the universe, scanning the atmospheres of Earth-like exoplanets, and more.

In short, the James Webb Space Telescope will undoubtedly make discoveries that will change humanity’s understanding of the universe – but first, it must reach its final destination. And if something goes wrong, there are no guarantees that scientists here on Earth can fix what’s wrong with it. This is very different from the Hubble Space Telescope, which, by virtue of its low Earth orbit, was served by NASA astronauts. five separate times Between 1993 and 2009.

However, because nothing should go wrong, scientists and engineers have spent two decades doing extensive preventive testing to predict anything and everything that could go wrong.

“When something is identified as a risk, there is a process that begins either with assessing that the risk is acceptable – meaning it wouldn’t be so bad if the thing one is concerned about happens – but if it is unacceptable,” said Massimo Stiavelli, head of the Webb mission office. “Risks are mitigated or eliminated,” in an interview with Salon. “So almost by definition, when a project like this is launched, there are no serious risks left, because you want to address all of them before you launch.”

Hence, the last delay.

[Related: Hubble’s enormous, ambitious successor is poised to change our understanding of the universe]

Of course, all these guarantees are not a guarantee, because no test yard is quite like reality – and unlike sports, for example, engineers do not get any training ground.

Launching the JWST is bound to be risky. First, there is the launch itself. On a date, no later than December 24, it will launch an Ariane missile with a JWST missile mounted on its nose. There will be lots and lots of vibration for the eighteen 46-pound mirrors that make up the observatory. Of course, the ability of these mirrors to withstand vibration has been extensively tested, Steavilli said, adding that nearly 20 years of preparation have ensured this launch goes smoothly.

“The observatory has been tested to be able to withstand the vibrations and sound waves associated with the launch,” Stiaveli said. “We know it could go on, but it’s still an exciting moment.”

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to the salon’s weekly newsletter, The Vulgar Scientist.

Another “exciting” moment, Staveli said, would be the deployment of the second sunblock and Half a day after launch.

“Unlike some of the other tests we’ve done, the sunvisor will of course be deployed in zero gravity,” Steavilli said. “And it’s hard to add zero gravity on Earth, so we had to use computer models to test that. As far as we know, it would work, but it would be nice to see it spread.”

After the initial set of major deployments, which will take an estimated six days to complete, Steavilli said he would be “personally happy”.

“But I’m sure the people who developed the machines won’t be happy until they see their machines fully operational six months after launch,” Staveli said.

Avi Loeb, former chair of Harvard University’s Department of Astronomy and author of “Extraterrestrials: The first sign of intelligent life outside EarthHe tells Salon that humans on Earth won’t know if there’s anything wrong with the instruments on JWST until he starts observing the sky — which can be a bit problematic.

“Unfortunately, its location at Lagrange Point II, four times the distance to the Moon, will not allow us to serve it as we did with the Hubble Space Telescope – which is 2,600 times closer,” Loeb said. “The response will depend on the method of failure; some problems can be partially resolved remotely.”

In fact, Staivelli said, the JWST team has practiced blindly routine exercises — meaning that engineers on the ground don’t know what problem they have to solve until exercise — to discover solutions to potential problems that may arise.

Stiavelli described these “rehearsals” as a process of “injecting anomalies,” then watching the team react to them and trying to fix them in real time. “The team is very well trained for such events,” he said. “If a major catastrophe or something goes wrong and it can’t be restored in the way I described – we’ll be in a bad shape.”

For example, if a massive asteroid collided or exploded during a JWST, there is no immediate alternative to the observatory. It will be difficult to get funding again to build another project. In addition, space observatories such as JWST do not have an insurance policy.

“It would be very expensive to build another one; some of the equipment that was used is no longer available, so it will not be easy. I am not qualified to answer exactly how much a duplicate will cost, but it will certainly be very expensive,” Staveli said. “The other factor is that in something like this that took so long to develop, a lot of people who might have worked on a particular component might have retired.”

Loeb agreed.

If the problem is more serious [than what can be fixed remotely]The astronomy community and NASA have to decide whether to invest the money needed to build another project.”

More stories about astronomy:

“Wannabe internet buff. Future teen idol. Hardcore zombie guru. Gamer. Avid creator. Entrepreneur. Bacon ninja.”